All articles

Logistics AI Gains Are Coming From Narrowly Defined And Highly Practical Use Cases

Michael Myers, Founder and CEO of Lully, shows how logistics AI delivers real value through small, well-scoped workflows and breaks down when teams automate flawed warehouse processes.

Key Points

AI in logistics often disappoints because teams chase flashy tools and automate broken workflows instead of fixing and improving how work actually gets done.

Michael Myers, Founder and CEO of Lully, frames AI impact through an operator’s lens, separating quiet wins in well-scoped processes from overhyped uses like layering LLMs over messy operational systems.

The strongest results come from small, constrained use cases and decision-science-driven planning that improve clean workflows first, then scale once trust and operational fit are established.

There’s a big difference between automating a clean, well-scoped workflow and automating something that’s already broken. A lot of what we see is people doing the latter and then being surprised when it doesn’t work.

In logistics and warehousing, the AI that actually moves the needle isn’t the kind making headlines. Real impact shows up in quiet places: narrowly defined workflows, clear handoffs, and automation applied where the process already works. That reality puts a sharp question in front of today's supply chain leaders: Are AI investments making a good operation better, or merely automating a broken one?

Michael Myers, Founder and CEO of warehouse orchestration platform Lully, comes at the problem with an operator’s mindset. A self-described "workaholic obsessed with warehouses," his perspective is shaped by years in industrial engineering and product roles at Third Wave Automation and ODW Logistics. That hands-on background grounds his views on AI in the realities of daily warehouse operations, where success depends less on novelty and more on whether a system fits the work as it actually happens.

"There’s a big difference between automating a clean, well-scoped workflow and automating something that’s already broken. A lot of what we see is people doing the latter and then being surprised when it doesn’t work," says Myers. To make sense of the market, Myers sorts AI applications into three distinct tiers.

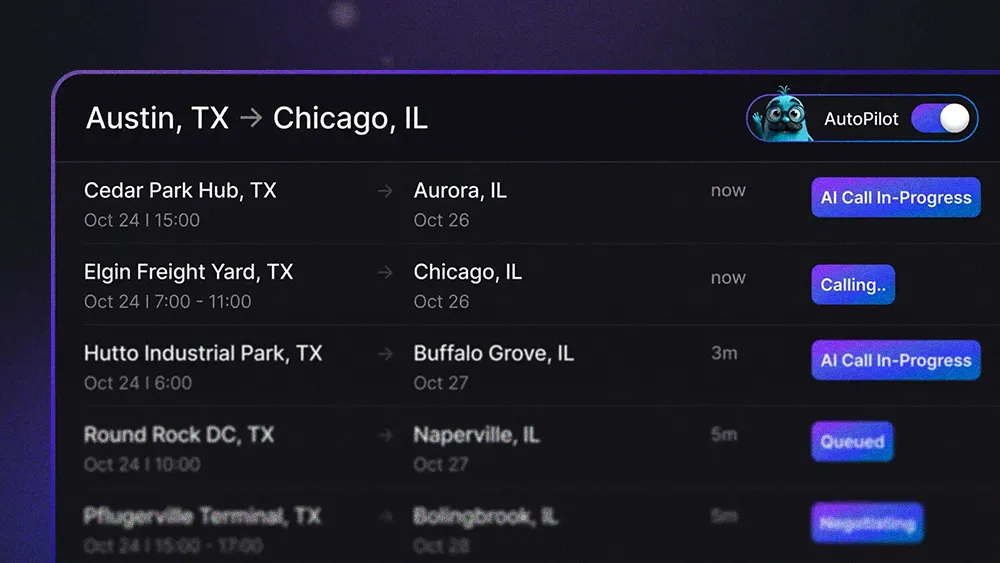

Quiet wins: The first includes simple, bounded successes. "There's been quite a bit of success using AI for well-defined processes with a clear start and endpoint, like appointment scheduling," notes Myers. "Some have had success with voice agents, others with browser-based agents interfacing with portals." These applications are driving tangible efficiency transformations across the industry.

A fool's errand: The second is a category of overhyped tools that often create more friction than they remove. "Layering LLMs over your data is a foolhardy approach," he continues. "Users have 'nested inquiries' because that's how they actually learn and work through a system. In those cases, this approach ends up being less efficient than just using a well-structured UI."

The real science: The third, he says, is where the real, substantive work is happening. "There have been talks of people using things like LLMs in planning, and that's typically gone pretty poorly. If you take more of an operations research, decision science approach though, people are finding success both intra-facility and across the wider supply chain."

Automating work constrained by an external system can make sense. Myers notes that problems start when that same logic is turned inward, using AI to formalize and accelerate a workflow that’s already broken instead of fixing what caused it in the first place.

Paving over cracks: "We've seen people try to apply that same logic to plan work in a supervisor-type capacity, and that becomes messy," he recalls. "It's the prime example of automating something that's bad. It’s a workflow that absolutely shouldn't even be occurring, and yet, instead of fixing the root cause, you go and automate it."

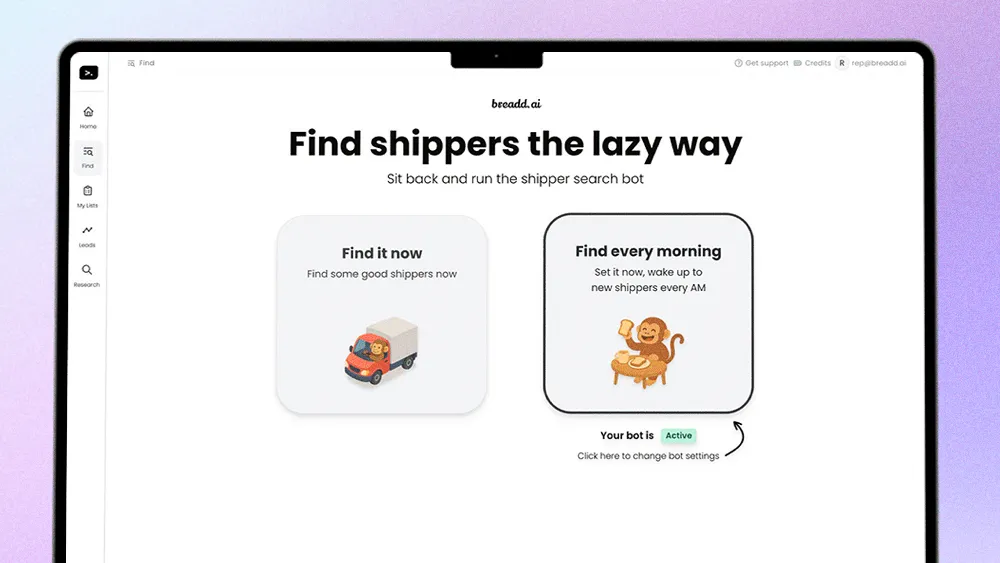

Free market research: For leaders fatigued by the hype, Myers recommends starting with small, low-risk moves that deliver immediate learning. "When you explore solution providers, you’ll find they build around very specific, finite use cases, and if your process can’t fit that mold, it gives you a chance to ask whether your way of working has drifted from the industry and if it’s still adding value." He also points to onboarding as an easy entry point, saying, "Maybe it’s just a sliver of AI, like providing a better interface for training or automating the initial SOP capture so your own people can polish it, and those are low-risk things you can stand up tomorrow to create momentum."

Practice what you preach: Myers puts his advice into practice. His substance-over-hype philosophy is the core operating principle of his own lean company. "On the lead capture side, we keep AI under control. Instead of just blasting thousands of emails, we leverage it to identify intent or opportunities which then drives manual outreach. We also use it for system design concepts, but we aren't bought into using it for full-scale code development yet."

Instead of fixating on the hype, Myers closes with a call to broaden the definition of AI itself. "There is more to AI than LLMs," he says. "Part of the problem is that people have settled into thinking of AI as just a prompt window you jam things into to get something back." He points to Instacart, whose order flow and task assignment systems are prime examples of operational decision science that people use daily without realizing it. In his view, companies that understand this "real" definition of AI are better positioned to thrive. "I think that providers that are building good, foundations-based businesses are going to be just fine. Businesses that are built on hopes and dreams and are potentially not finding product-market fit very fast are probably going to have a tough go at it."

The downside to the current hype cycle, Myers notes, is that the noise from cold outreach makes it harder to have genuine conversations. Progress is still possible when the intent is right. "When you actually get the real conversation going and you aren't in it to just sell them a thing but you're there to try and help, people want the technology, they want the solutions, but they struggle to figure out how to get going." This, he reflects, is just the newest version of a challenge physical automation has faced for 60 years.