All articles

How Academia And Industry Are Joining Forces To Fix Manufacturing’s AI Adoption Gap

Paul Lavoie, VP of Innovation and Applied Technology at the University of New Haven, outlines how universities are stepping in to help manufacturers turn AI and automation into real productivity gains.

Key Points

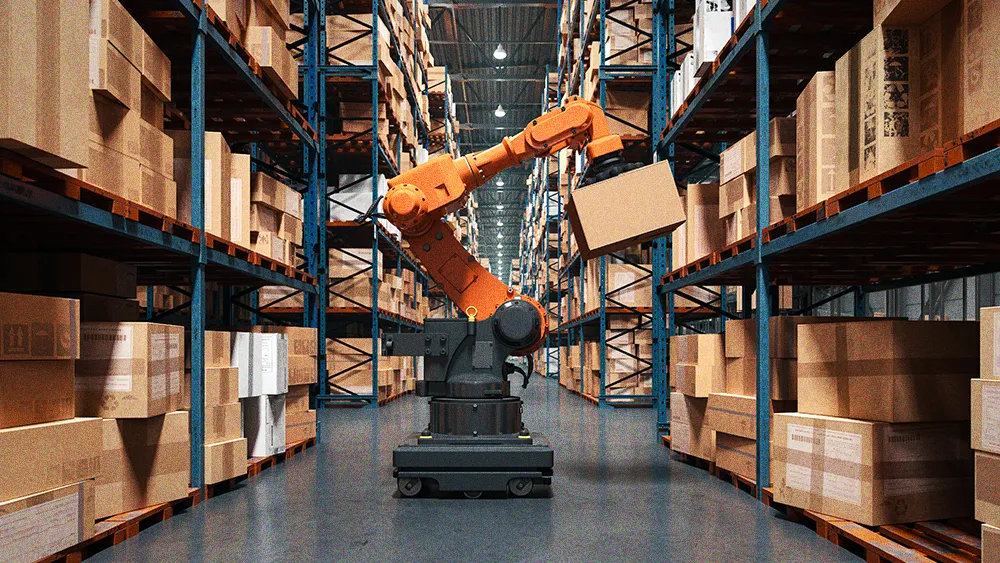

Manufacturing faces a persistent labor shortage, but the bigger blocker is an adoption gap that keeps AI, robotics, and automation from translating into real productivity.

Paul Lavoie, Vice President of Innovation and Applied Technology at the University of New Haven, describes how academia steps in where industry planning and government continuity fall short.

An industry-driven university model engages companies, educates them on emerging technologies, and enables adoption, with AI and robotics as the non-negotiable levers for growth.

Industry is worried about production, government is temporary, but universities are forced to plan four, five, six years ahead. That gives us a rare opportunity to lead and help industry prepare for what’s coming.

Manufacturing leaders are running out of options. The skilled labor shortage isn't going anywhere, and productivity gains won't come from hiring alone. That leaves technology as the only real path to boosting productivity. Yet for many companies, the issue isn't a lack of technology, but a struggle with its adoption. Closing that gap requires a new kind of leader, one focused on translating technology into real, workable change on the factory floor.

Paul Lavoie sits at the intersection of technology, government, and academia. As Vice President of Innovation and Applied Technology at the University of New Haven, he is building a 130,000 square foot Research and Development Park designed to tackle the manufacturing adoption gap head on. The effort reflects a broader shift in how universities are stepping beyond talent development to actively shape how industry understands, tests, and adopts emerging technologies.

"Industry is worried about production, government is temporary, but universities are forced to plan four, five, six years ahead. That gives us a rare opportunity to lead and help industry prepare for what’s coming," says Lavoie. The gap between today’s needs and tomorrow’s demands shows up first on the front lines. Universities are already welcoming the class of 2029, but many of the companies that will eventually hire them struggle to plan that far ahead. Lavoie points out that small and mid-sized manufacturers often can’t model the return on technologies they don’t yet understand. When he asks how AI will shape their business in 2030, the response is often the same: blank stares.

Built for business: One answer is taking shape through the University of New Haven’s Center for Innovation, Applied Technology, where work is organized around market demand rather than academic silos. While the physical Center is still taking shape, its industry-driven model is already being put to work through active partnerships and live projects. "Companies don’t come to us with a curriculum problem. They come with a business problem," Lavoie says. The Center is designed to act as a translator and enabler, helping manufacturers evaluate what technologies actually matter and how to adopt them.

Projects on tap: "Most companies know AI and automation exist, but they don’t know where to start or how to judge what’s real," he explains. The response has been immediate. "I’m not worried about demand," Lavoie adds. "I’m going to run out of students before I run out of projects."

The Center’s reach already spans a wide range of partners, from large manufacturers like Electric Boat and Lockheed Martin to small and mid-sized firms. Those partnerships bring real business problems onto campus, not just engineering challenges. In one case, an economics professor led a tariff mitigation project for a manufacturing company, underscoring how the Center pulls from across the university to solve practical industry needs while preparing students for the realities of modern manufacturing.

Building the blueprint: The Center’s industry-first flexibility is intentional, not improvised. Its default blueprint is the product of extensive listening sessions with manufacturers, giving Lavoie confidence even as he leaves room for market needs to shape the final design. "Industry will ultimately define the floor plan," he says. "But the plan I have today is grounded enough in their input that if someone wrote a $25 million check tomorrow, I could build it and be confident we got it right."

In Lavoie's view, his strategy is built on a clear, three-step model. He says that after engaging companies, universities are uniquely positioned to handle the second step: educating them on new technologies and de-risking the process. The third step, enabling adoption, requires smart, proactive government incentives that help companies learn to properly evaluate and implement new tools for digital transformation.

Ultimately, Lavoie believes the biggest barrier to progress is psychological. He encourages leaders to change the fundamental question they ask, replacing a reflexive 'that won't work in my business' dismissal with a curious 'how can this work in my business?' exploration of potential. He concludes by ranking the productivity levers he believes manufacturers can focus on, providing a clear hierarchy for their efforts.

"The key drivers of productivity are clear: artificial intelligence and robotics are at the top of the list, followed by additive manufacturing and digital transformation. But make no mistake, AI and robotics are the non-negotiables. They are the only way we will increase productivity and efficiency, because we don't have people."